Abstract

Dyeing PA fibres and their blends is a real challenge to textile manufacturers! In practical use it is known that for sophisticated PA dyeings the following becomes essential during the whole dyeing process: an accurate pH value and temperature control. For producing high-quality fabrics, levellers are required that have affinity to the dye or to the fibre, depending on their task.

Products with dye affinity are used as levelling agents and have a pseudo-cationic character; fatty amine ethoxylates are very frequently used. They form a dye-auxiliary complex, dissociating bit by bit in the dye bath with increasing temperature, facilitating the exhaustion of the dyes onto the PA fibre.

Auxiliaries with fibre affinity are often based on sulphonic acids and thus are anionic. They are normally applied for preventing streakiness on PA fabrics, since they exhaust on to the fabric instead of the dyes in the dye bath. For achieving good dyeing results on streaky-dyeing fabrics, even with a critical dye trichromate, the right auxiliary combination has to be found. In this article such an auxiliary system is presented, with SARABID IPD and IPF, which also facilitates the even dyeing of very critical dyeings without any problems.

Introduction

Today’s market puts high demands on modern textiles made of polyamide. The new CHT levelling-agent concept can fulfil these demands. Our innovative product system, consisting of SARABID IPD and SARABID IPF, accurately regulates the dyestuff exhaustion and helps guarantee level dyeing results, even on barré dyed polyamide articles.

Module Component 1: SARABID IPD

Influence on the levelling capacity

SARABID IPD has affinity for the dye and forms a dye-auxiliary-complex with the anionic dyes, which dissociates bit by bit in the dye bath with increasing temperature, enabling the dyes to exhaust evenly on to the PA fibre. SARABID IPD promotes the exhaustion behaviour of the individual dye components throughout the complete temperature profile and provides optimum bath exhaustion. For demonstrating the efficiency of SARABID IPD, some test methods are described in the following chapters. The levelling capacity of a levelling agent is illustrated by means of a step test, verifying both the levelling effect (mobility of dyes on the fibre) and the synchronisation effect (adjustment of dye exhaustion speed).

Test Description

In a step test, individual dyeings are removed at different temperature intervals during the dyeing process and replaced by an undyed sample. For the test series, polyamide material of the kinetic fibre type 3-4 was used, ie. a PA fibre type with normal exhaustion (kinetic fibre type 1-5 is determined with a simple dyeing test, which may be requested separately).

Acid dyes from the BEMACID N range were selected as test dyes. BEMACID N dyes are acid dyes of medium size with one sulpho group. The migration capacity of this dye class is moderate but can be clearly improved by adding a leveller with dye affinity. This is shown in the comparative dyeing.

The test was carried out on the laboratory dyeing machine Mathis- Labomat:

100 % PA 6.6 knitwear, ready for dyeing

LR 1:10

Initial dyeing temperature: 30°C

Heating rate: 1°C/min

pH 5.5 with NEUTRACID BO 45 (buffer system)

0.25% BEMACID Yellow N-TF

0.50% BEMACID Red N-TF

0.75% BEMACID Blue N-TF

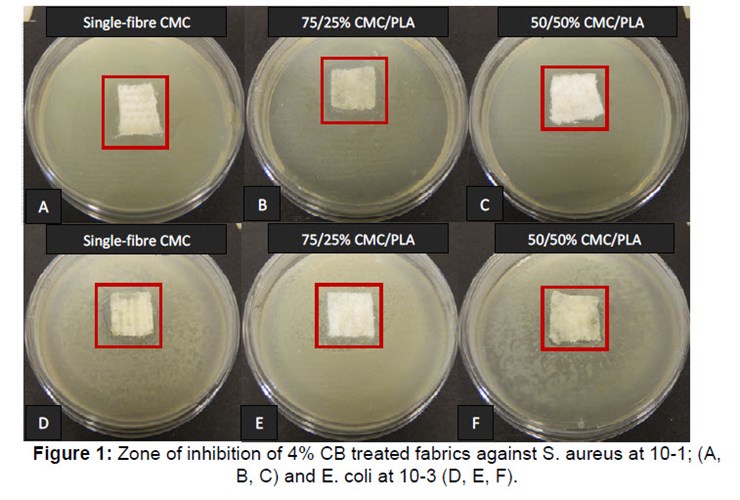

The result of the step test (Figure 1)

shows both an even as well as a synchronous dyestuff exhaustion with SARABID IPD: In combination dyeings, SARABID IPD aligns the exhaustion behaviour of individual dye components, since it controls the exhaustion speed of the dyes in the heating phase and promotes an even dye distribution at boiling temperature in the migration phase. The same applies for 1:2 metalcomplex dyes. Besides the levelling capacity, the migration capacity of a levelling agent is also of major importance in PA dyeing.

Influence on the migration capacity

SARABID IPD increases the migration capacity of the dyes by reducing the dye affinity to the fibre. This is tested by a migration test.

Test Description

In a first step a dyeing, using a poorly migrating acid dye, is produced in the exhaust process on a 100 % PA 6.6 ready for dyeing knitwear (fibre kinetic type 3-4, normal exhaustion). In a second step a blank dyeing is simulated at a 1:1 ratio with the undyed PA 6.6 knitwear ready for dyeing. Afterwards the levelling between the originally dyed and undyed part is evaluated. The closer the colour sample is adapted to the colour depth of the undyed sample, the better the migrating effect of the auxiliary. The levelling capacity can also be evaluated in this test, due to the total visual evaluation of the dyeing.

Step 1: Original dyeing

The dyeing was carried out on the laboratory dyeing machine Mathis-Labomat:

100 % PA 6.6 knitwear, ready for dyeing

LR 1:10

Initial dyeing temperature 40°C

Heating rate 1°C/min

Constant pH 5.5 with NEUTRACID BO 45

0.70 % BEMACID Navy N-5R

98°C, 45 min

Then rinse warm and cold

Step 2: Levelling test

The dyed PA fabric is treated blank at a 1:1 ratio with the undyed PA fabric using constant process parameters in the following way:

LR 1:10

Initial dyeing temperature 40°C

Heating rate 1°C/min

Constant pH 5.5 with NEUTRACID BO 45

x % SARABID IPD

98°C 45 min

Then rinse warm and cold

Step 3: Visual evaluation of the migrating and levelling effect of the dyeing without auxiliary in comparison with the dyeing with SARABID IPD.

In the migration phase SARABID IPD promotes an even distribution of the dyes at boiling temperature (Figure 2).

Product Properties of SARABID IPD

General properties: promotes surface evenness

Low foaming, environmentally friendly levelling agent for acid and 1:2 metal complex dyes

GOTS-listed for PA blends

Improves the combination behaviour of acid dyes

Excellent suitability for DD carpets to achieve high contrasts

Reduces the dye’s strike rate on quickly absorbing polyamide fibre types, in particular in the carpet and automotive sector providing thus an even application of dyes throughout the complete dyeing process

Does not contribute to fogging

Dyes polyamide/wool blends for improving the tone-in-tone dyeing with selected acid dyes

Ensures a level dyeing, even on unlevel dyed articles.

Preferred Application of SARABID IPD in polyamide dyeing

Clothing: hosiery, socks, outdoor, sportswear and swimwear, underwear, etc

Home textiles: residential and commercial carpets (eg. differential dyeing, high contrasts), upholstery and furnishing fabrics, etc

Technical textiles: tapes, straps, sewing threads, ropes, filters, etc.

Module Component 2: SARABID IPF

SARABID IPF is the anionic component and has affinity for the fibre. It levels differences in affinity caused by the material because the components with fibre affinity stick to the cationic charges of the polyamide fibres before the dye can exhaust unevenly onto the fibre. The component with pure fibre affinity shows no synchronisation effect and has no influence on the exhaustion behaviour of the dyes.

To achieve optimum efficiency SARABID IPF is added prior to the dye.

Influence of the pH value and temperature on the exhaustion capacity

The best exhaustion capacity of SARABID IPF is in the acid pH range and at boiling temperature. The exhaustion capacity is demonstrated with the example of 2.0 % SARABID IPF on a PA 6.6. knitwear (normal exhaustion), LR 1:10, heating rate 1°C/min. The exhaustion curve shows the following:

The exhaustion capacity decreases towards the neutral range; with a higher temperature the percentage of bath exhaustion of SARABID IPF increases.

Thus, the exhaustion curves demand the following dyeing process parameters: if affinity differences caused by the material are to be efficiently prevented in polyamide materials, SARABID IPF is to be added to the dyeing liquor at the beginning, the pH value is adjusted to approx. pH 4.5 and the dyeing material is pretreated with the stated additives at boiling temperature for 10 - 15 min. Then, the material is cooled down to the required initial dyeing temperature in accordance with the polyamide fibre quality in use. Only then is the pH value corrected depending on the dye selection, and the dye and the levelling agent with dye affinity – SARABID IPD – are added. SARABID IPD reduces the exhaustion speed of the dyes and thus has a levelling effect. This complex dyeing process is well known as the so-called ‘pre-boiling method’ (Figure 3).

Elimination of streakiness caused by the material: influence of the exhaustion degree of dyes with the presence of SARABID IPF in the dye bath

SARABID IPF shows the best exhaustion behaviour on to the polyamide fibre at a pH value of 4.5 and a temperature of 98°C. But how do dyes behave in the dye bath? The dye-exhaustion capacity is demonstrated with the example of C.I. Acid Red 199 (0.3 % application amount) together with different application amounts of SARABID IPF in the dye bath on a PA 6.6. knitwear (normal exhaustion), LR 1:10, heating rate 1°C/min, pH 4.5. The exhaustion curve shows the following (Figure 4):

The exhaustion degree of the dye is clearly slowed down with the presence of SARABID IPF. The higher the application amounts of SARABID IPF, the more strongly is the dye held back in the bath. A positive effect is that these properties level out differences in shade.

SARABID IPF particularly eliminates streaks that are caused by structural differences in the PA fibre. Dyeings with an even surface are produced. The dyeing example shown in Figure 5, dyed with 1:2 metal-complex dye, shows the

comparison:

Compatibility with a levelling agent with dye affinity

SARABID IPF is compatible with SARABID IPD. Both products have a good migrating and levelling effect if used together in the dye bath. Product properties of SARABID IPF General properties: covers streakiness; levels differences in affinity caused by the material when dyeing PA with 1:2 metal complex and acid dyes.

Low foaming, environmentally friendly

GOTS-listed for PA-blends

Efficient as an anionic retarder. SARABID IPF slows down and homogenises the exhaustion of dyes in the heating phase promoting thus their evenness

Reduce or minimise contrasts for PA DD-carpets with acid dyes

When dyeing fabrics with strong affinity differences we recommend either carrying out the known but time-consuming ‘pre-boiling method’ or carrying out a special dyeing process together with MEROPAN LS. This is a special acid donor being added without moving the pH value abruptly into the acid dyeing range (more details can be taken from the separate CHT information brochures on this special dyeing process)

No impact on the colour and light fastnesses

Preferred application of SARABID IPF in polyamide dyeing

Clothing: above all sportswear, swimwear, etc

Home textiles: residential and commercial carpets and carpets for personal transport (eg. for differential dyeing carpet fibres in order to prevent contrasts)

Is There a Simpler Alternative?

Many dyers, particularly commission dyers, presently work with varying polyamide qualities. The fabric is delivered to the company in the morning and in some cases needs to be finished and ready for delivery by the next day. They do not have the time to examine individual polyamide qualities in terms of their kinetic fibre-dyeing behaviour and material differences caused by the structure by means of pretrials in their own laboratory.

For facilitating just-intime finishes we additionally developed a combination product, consisting of SARABID IPD and SARABID IPF, which levels out and prevents streakiness, particularly on varying PA qualities and in general for an easier handling and lower storage cost. SARABID IPM unifies the product properties of SARABID IPD and SARABID IPF.

Product properties of SARABID IPM

General properties: promotes surface evenness and levels out streakiness caused by the material.

Multifunctional leveller for dyeing polyamide

User-friendly

Low foaming, environmentally friendly

GOTS-listed for PA-blends

Preferred application of SARABID IPM in polyamide dyeing

For varying polyamide qualities

Conclusion

CHT offers textile finishers a new attractive package of innovative levelling agents for polyamide. The system is based on modules for highest flexibility and the new product range is designed to help textile finishers meet top quality requirements.